Global awareness and concern of greenhouse gas emissions has led automotive original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), governments and individuals to consider more eco-friendly alternatives to reduce the dependency on fossil fuels. As a result, the sales of electric vehicles (EVs) are rapidly increasing and in 2018 the global EV fleet surpassed 5,1 million. Some estimations indicate that a total of 2,5 million EVs were sold in 2019, thus representing a 50% increase of the entire fleet. Some of the main contributors to the increasing sales are decreasing prices combined with governmental incentives and favourable policies towards EV buyers and owners.

EVs are mainly powered by lithium-ion batteries, which we will refer to as electric vehicle batteries (EVBs). In general, EVBs should be replaced once their total capacity is reduced to 80% of their initial capacity, which usually occurs after the vehicle has been powered for approximately 5-10 years, or about 100.000 km to 150.000 km. Once an EVB has reached its maximum capacity, automotive OEMs are responsible for collection with the purpose of disposal e.g. remanufacturing or recycling. Reverse logistics of EVBs require certain technical and administrative capabilities that are not amongst the core competencies of automotive OEMs. Thus, these activities are outsourced to external actors, such as third-party logistics providers (3PLs) and recyclers.

EVBs are still an emerging technology with rapid technological developments, therefore the EV industry shows great potential for market growth. But currently, the volumes of EVBs entering their end-of-life are too low to develop functioning business models and collection networks. However, the volumes are expected to hit critical mass during the upcoming years. Until then, there are many challenges related to reverse logistics that the industry has to overcome in order to establish sustainable closed-loop supply chains.

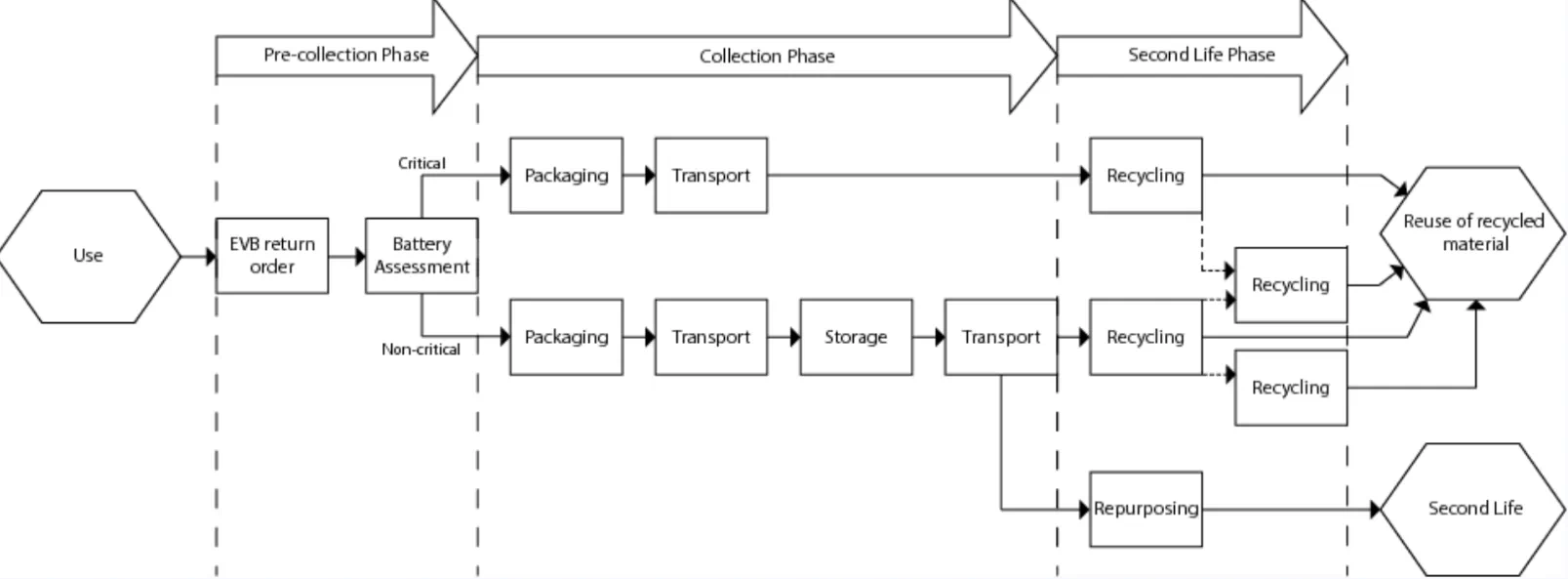

Critical and non-critical EVBs

EVBs entering the reverse chain have to be assessed by a certified dangerous goods expert to determine whether the EVB is to be considered critical, or non-critical. Non-critical batteries can be either damaged or not damaged, while critical batteries are severely damaged, and their state is considered not to be stable. Jan Arff, managing director at Ecobat Logistics clarifies that critical EVBs are batteries that cannot be classified as safe and that handling such batteries are subject to special approvals. Many EVBs being returned today are in fact damaged, defective or critical since few EVBs has reached their end-of-life naturally. Jan Arff further explain that “50 to 60% of the batteries coming back now are damaged or even critical due to having an accident or having a production issue”. According to Christian Moser, who works in automotive logistics at DB Schenker, one of the most important aspects for the future of reverse logistics of EVBs will be that certified dangerous goods experts are easily accessible. They should be able to promptly arrive at the designated location in order to determine what can or has to be done with the battery.

The battery assessment is an important step as it determines how the EVB is going to be handled. Misjudging the state of an EVB can have severe consequences, chemical reactions can cause the battery to catch fire, or even explode and once an EVB is burning it can be difficult to extinguish. Even if an EVB would be declared as non-critical, it is possible that the status of an idle EVB changes over time. An employee of a 3PL clarifies that “you can have an EVB on the shelf for half a year and nothing happens and when you take them out, the movement causes a chemical reaction”. Even though non-critical EVBs have less restrictions, they still require special handling. In order to minimise the risks associated with handling critical EVBs, special precautions are needed, such as special packaging, storage, routing and transportation.

An example of a battery pack

Risks in the collection phase

As for storage, national, regional and local authorities have a range of demands to ensure safety, which makes storage one of the most cumbersome activities. Examples of such requirements could be sprinkler systems, working with gas masks, continuous observation and disclosed quarantine zones. An example of specific requirement would be the distance between used EVBs in storage racks, for instance, 6 meters between each row and 1,2 meters between individual layers. This shows the difficulties in acquiring proper facilities for storing used EVBs as it requires sophisticated equipment, processes and a lot of space. According to a representative of a recycling company “storage is just costing money and is a safety risk”, even though this might be true, most collection networks are so underdeveloped that storage is unavoidable. Most recyclers do not accept single batteries, but instead have a minimum limit of 1-2 tons. As a result, many smaller reverse chain actors, such as dealerships and transportation companies need to store EVBs of uncertain state outdoors.

EVBs are heavy and weigh approximately 100 – 600 kg each and are not compatible with standard pallet sizes, thus complicating consolidation and decreases overall utilisation of the trucks collecting them. Critical batteries have to be transported in special transportation boxes. These transportation boxes are required by law. They are equipped with acid proof casings and oftentimes have a build-in fire extinguishing system. These components make the boxes quite expensive and depending on size can cost up to 10.000 Euros. Usually a firm should invest in around 20 boxes to smoothly operate transportation. However, to avoid binding capital, some companies have started renting boxes and, in some cases, sharing boxes with each other.

Figure 1 Reflection of reverse logistics supply chain

To carry out transportation, firms need to adhere to instructions from municipalities. Such instructions can include the avoidance of roads and especially tunnels which the municipalities deem as too dangerous for the general public. One estimation says that approximately 2% of all returned EVBs will be critical, mainly originating from defects or accidents. Regarding critical batteries, Achim Glass, Global Head of Automotive Vertical at Kuehne + Nagel, explains that “The current volumes are manageable to organise, but in five years you will need ultimate systems as it will no longer be possible to administer from a manpower perspective, it is just too big, too large and too complex”. Non-critical EVBs have less restrictions, but still require special handling and are considered as both dangerous goods and waste. Regulations and legislations regarding transportation of dangerous goods and waste differ from country to country. Making it difficult to operate across borders due to a heavy administrative workload. Thus, in Europe, companies rely on the Accord Dangereux Routier (ADR). The ADR defines the mode of transportation and the right packaging for the transported product. Firms are dedicating personnel to ADR as these requirements are continuously updated. Achim Glass said, “we have three people studying these regulations, all the time”. This illustrates the complexity and importance of understanding the different regulations. According to Wassilij Weber who is working for Interseroh, a company that amongst other waste material is specialised in collection, recycling and transportation of waste EVBs, such know-how related to regulations currently represents one of the largest entry barriers for new market entrants.

Main challenges related to recycling

The aforementioned challenges have limited most transportation companies to operate locally, which is problematic since far from every country (in Europe) has a recycling facility capable of recycling EVBs. “Recycling facilities are usually designed for specific types of goods, such as lithium-ion batteries, but at the moment, there are not enough batteries to operate such facilities that covers the whole scope”, says Weber. Instead, many countries have facilities where EVBs are dismantled into modular level, the modules are then sold to recyclers all over Europe. This brings us to another problem, only a small portion of the EVB is being recycled, with the main areas of interest being the recycling of copper, cobalt, nickel and aluminium. Lithium is one of the metals that is not recycled today as the process has to be refined in order to make it economically justifiable. The representative of a recycling company further explains “if you can buy virgin lithium cheaper than recycled, I think most companies will buy the virgin lithium. It is also a question about quality” showcasing that more efficient recycling methods have to be developed to make EVB recycling sustainable. In comparison, the similar market for used lead-acid batteries have achieved a scenario where secondary lead is actually cheaper than importing lead from the primary source. However, the comparison is not completely fair as lead acid batteries are highly standardised both in terms of composition and design. As Jan Arff puts it “we pay money for lead acid batteries, when you look at lithium batteries, people have to pay to get rid of those”.

Nowadays OEMs in most industries are taking end-of-life activities into consideration when designing a new product in order to facilitate disposal. However, the EVB industry does not seem to follow the same pattern as technological advancements are being made with short time intervals by competing battery OEMs who wants to optimise their EVBs in terms of design and composition. Consequently, there are thousands of non-identical EVBs on the market, battery OEMs are also secretive about battery chemistry and designs which further complicates the reverse logistics. A major problem is insufficient marking, EVBs rarely have any information regarding the battery chemistry, forcing recyclers to make manual decisions for every single battery. Proper marking and labelling would enable recyclers to instantly choose the best recycling method for each battery, which will be a necessity once the volumes of returned EVBs starts rising. Additionally, activities related to reverse logistics could be facilitated through a more transparent dialogue with OEMs, and through achieving standardisation in battery shape, size and design.

Possibilities for remanufacturing

As recycling technologies are lagging behind, the idea of providing a second life for EVBs becomes a really interesting option. Especially since EVBs still possess about 80% of their capacity when they are discharged from the vehicle. During our research, it became evident that no real solution for remanufacturing has been developed. Instead, most initiatives are still at a research or pilot level, one trend is that an increasing amount of EVBs are picked up by research institutions, which is positive.

According to Christian Moser, “The technology is improving, so I think there will be some business model, but not on the base of today’s technology”. This illustrates that there is uncertainty connected to earliness of technology present in the industry. Some actors even question whether lithium-ion will still be the predominant technology in 10 years. Similarly, the approximate of one thousand different EVB chemistry compositions further complicate the process of choosing the most suitable second life application. There are many promising areas for remanufactured EVBs, both in stationary and mobile applications. For instance, modules could be extracted in order to create mobile energy providers. Modules of high quality could be reused in electric vehicles or for stationary applications where uninterrupted power supply systems are needed, or where emergency power supply is crucial, e.g. in hospitals or server facilities. Modules of lower quality could be used for basic stationary applications, such as servers for solar panels or windmills.

Currently the vast majority of the industry is simply discussing and researching the possibility of remanufacturing. Collaboration is necessary in order to establish proper alternatives for second life applications, a recycler stated that “No company can do it by themselves, it has to be a group of companies that develop these concepts together”. Nevertheless, battery OEMs will have to be involved in the process due to their knowledge of the battery management system.

Creating a healthy reverse chain for EVBs

In conclusion, it is apparent that reverse logistics is highly influenced by governmental regulations, legislations and incentives. As the market matures, regulations and legislations will likely be strengthened. With stricter requirements, the industry would have to develop more efficient collection systems and more advanced recycling technologies.

Until volumes increase, collaboration and sharing best practice throughout the reverse chain is essential. Many 3PLs and recyclers today are part of research and focus groups where possible solutions to current challenges are discussed. It is important that such groups include both battery and automotive OEMs as they have the power to adapt the batteries in order to facilitate and standardise EOL activities. Without standardisation it is hard to set up lean collection systems. Instead, the industry has to act agile and adjust their processes to each individual battery. Operating an agile supply chain requires know-how that is not easily obtained. An example of such know-how would be that firms need to stay informed about different transport legislations.

Once volumes increase, firms will have to transport more batteries between different countries with diverse legislations. As a result, firms are forced to devote valuable personnel to study these legislations to ensure compliance. Centralised recycling hubs would limit the number of borders that need to be crossed, thus lowering administrative costs. Additionally, investments have to be made into transportation boxes as EVBs have to be transported in a safe manner. Therefore, such boxes will constitute one of the core investments for firms who want to transport and/or store EVBs. This is highly relevant for critical batteries, but also for non-critical batteries as their state can change during transportation and storage.

Related content

Consortium Project - Yesterday's scrap is tomorrow's gold

Electric Vehicle Challenges & Opportunities for European Remanufacturers

Steady growth for worldwide battery electric electric vehicle fleet

About the authors

Alexander Ziemba and Fabian Prevolnik both earned their Master’s degree with a major in business administration in 2019. They studied International Logistics & Supply Chain Management at Jönköping International Business School, Sweden. Together they authored the master thesis: The Reverse Logistics of Electric Vehicle Batteries, on which this article is based.

Alexander Ziemba

Project Management at Giesecke+Devrient

Alexander works in project management in the purchasing department for Giesecke+Devrient, a leading company providing security technology both for the physical and digital scope of money transactions.

Fabian Prevolnik

Logistics planner at Metso

Fabian works at Metso, an industrial company which is providing technical solutions and services for several industries. He works in project execution and is a part of the logistics department for process equipment used in the mining industry.